When in 1789 the first Federal Congress was called to order, slavery was not supposed to have been on the agenda. James Madison, “Father of the Constitution,” had worked hard to keep this divisive issue out of sight. One Madison compromise was passing the constitution with a provision barring Congress from regulating the slave trade for 20 years, until 1808.

When in 1789 the first Federal Congress was called to order, slavery was not supposed to have been on the agenda. James Madison, “Father of the Constitution,” had worked hard to keep this divisive issue out of sight. One Madison compromise was passing the constitution with a provision barring Congress from regulating the slave trade for 20 years, until 1808.

Imagine the surprise of most members of Congress when groups of abolitionists submitted petitions calling on them to address the issue of slavery. Most of these petitions were submitted by Quaker organizations who argued that regulating the slave trade was different than abolishing it.

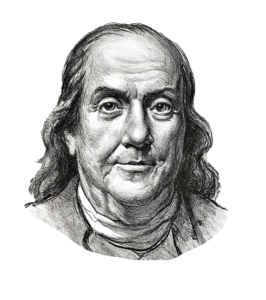

Benjamin Franklin, who was a “Founding Father” for his service on the 1787 Constitutional Convention, served as the President of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. In 1790, he presented a formal abolition petition to Congress.

Other groups, many associated with the Quakers, also presented petitions to the new Congress.

The possibility that the Congress might take on the cause of slavery evoked strong responses from Southern representatives1…

Mr. Tucker, South Carolina:

“Do these men expect a general emancipation of slaves by law? This would never be submitted to by the southern states without a civil war.”

“If judge was to assert such doctrine his existence would not be long. It would blow the trumpet of civil war.”

Mr. George Jackson, Georgia:

“The master has a property over his servant the same as over his slave. Whether religion sanctifies slavery will not to pretend. If these good people would search out Bible in Genesis, slavery was from the original.”

1Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, 1789-1791. Vol. XII: Debates in

the House of Representatives: Second Session, January-March 1790. edited by Helen E. Veit, Charlene Bangs Bickford, Kenneth R. Bowling, and William Charles Di’Giacomantonio. (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994): 296, 306, 308.